State Crime And Police Cover Up; A Reappraisal Of Infamous Cases: Twickenham Attacks; Part Three: McDonnell’s silent assassination

The Metropolitan Police say that they received a tip-off that Levi Bellfield owned a Ford Courier, and this is how he became the suspect in the Delagrange murder case (see the second part of this mini series). That a Ford Courier was photographed parked by Twickenham Green was the strength of all the evidence against him. Likewise, the evidence to convict him of the murder of Marsha McDonnell, in February 2003, was equally weak. Bellfield owned a Silver Vauxhall Corsa, and the prosecution against him argued that this car was seen in bus mounted CCTV footage, captured from the very vehicle that McDonnell was travelling on before she was killed. In truth, this means of incriminating him was incredibly dubious.

There was one image – one solitary image – of the car where a single letter of the registration plate could be discerned, so said the Metropolitan Police. It was the initial letter, said to be a “Y”, and it narrowed the field of a search to 178 vehicles. Apparently, 177 owners were interviewed, and gave the police an alibi – but then, of course they would – leaving Levi Bellfield apart, who never, we are told, answered police questions except to say “no comment”.

This image from the Channel 5 programme shows the Corsa approaching the bus – but from the front and on the other side of the road as usual, or overtaking from the rear?

But the problem about this process of elimination is that it very likely started off on the wrong foot. The defence at Bellfield’s trial produced its own expert witness who argued…

that motion blur, lighting and picture compression could lead to limitless image distortions and that the absence of any other stills for comparison purposes meant the first character could be any number of letters, such as R.

(Source: Your Local Guardian).

Indeed, the prosecution even owned that this letter could be an “X” just as well as it might be a “Y”. Even on these merits, as a standalone case, it is highly doubtful that Bellfield should have been convicted of killing Marsha McDonnell.

This image, also from the Channel 5 programme, is implied as being another one showing the Corsa. It appears to be captured by a camera inside a bus. It is not known if it is this image, or the one above (or indeed some other undiscovered or unreleased image) that was examined so as to see a letter “Y” in the number plate.

As well as for the attempted murder of Kate Sheedy (see the first part of this mini series), and the murders of Marsh McDonnell and Amelie Delagrange, Levi Bellfield stood trial for attempted murder of yet another woman, and also for an attempted kidnap of another. In these two additional cases, Bellfield was identified by witnesses as being at the scene of the crime, and indeed executing it. It is clear that the three convictions of Bellfield for murder and attempted murder were secured by prosecuting these five cases at the same time, and then, from these jointly, having the jury perceive a “compelling” single reason to identify Bellfield as the sort of person who would commit a murder. The jury was also to be worked upon by an apparent fact of the involvement of his vehicles in three cases being too much of a coincidence; it was invited to understand that the sighting of a vehicle that police said belonged to Bellfield incriminated him in the same way as seeing him bodily involved in the way he was accused in the additional two cases.

Ironically, the jury couldn’t reach a verdict on Bellfield committing these additional crimes, and so in fact the whole construction against him fell down – or it should have done. That Bellfield was convicted of the murder of McDonnell and Delagrange, and the attempted murder of Sheedy appears to be due to the prejudice created by the details of the other charges, without the encumbrance of the same sort of detail in these three cases that would have created doubt.

It appears to the author that, ultimately, the Metropolitan Police decided that Bellfield was going to take the rap for whatever he could be held responsible for (including, later, the murder of Milly Dowler) – and we are aware of circumstances that might have made it easier for police to bring this about. Bellfield was a Metropolitan Police informant. Indeed, as it has been said previously in this series, the Sheedy attack is at risk of betraying itself as being a specific incident carried out to frame him. But before there is any more exploration of this idea, there needs to be a full examination of why the accusation against Bellfield on the count of murdering McDonnell is not sound.

The Metropolitan Police said that Bellfield picked out Marsha McDonnell, in the same way he did Kate Sheedy, by observing her sitting on a bus when he encountered it. He then followed the bus in his car until McDonnell disembarked. Significantly, although this bus-following is what he supposedly did in all the three murder and attempted murder cases, it was only in the McDonnell one where police offered any evidence that it was Bellfield’s modus operandi. The method was supposedly captured by bus mounted CCTV cameras, and at the time of the trial, the Evening Standard reported that police had cobbled together stills – not footage, please note – with moving pictures of their own creation to tell the story their way:

The prosecution used computer graphics spliced with stills from the bus’s CCTV to recreate Miss McDonnell’s final journey on the 111.

The footage showed Bellfield’s silver Vauxhall Corsa following the bus, and then slowly overtaking it when it stopped to let Miss McDonnell off.

The car is then seen pulling into a side road.

The problem with this account is that, according to timings given by police, McDonnell must have got off the bus at a stop which was less than a minute’s walk from a crossroads. The stop was in a street called Percy Road, and McDonnell would have to walk to the intersection, which was with Priory Road. Priory Road, of course, is the street upon which she lived, and along which her journey would have taken another four minutes – roughly. However, Bellfield, not knowing where McDonnell lived, having merely picked her at random after seeing her on the bus, couldn’t have predicted in which of the four directions available to her McDonnell would have proceeded. How, then, did he know which “side road” ahead of the bus stop he would need to station himself in order to ambush her?‡

It appears that the attack on McDonnell happened very chronologically close to the time she was found by one of her neighbours. This was at 00.30. The person who discovered McDonnell was woken by a thud, and went outside to find her still alive, but in a state of distress. She had been struck by a blunt instrument.

The time of this discovery, with McDonnell only a matter of yards from her own door, was cause for a mystery, because it occurred thirteen minutes after she had gotten off the bus, and it only should have taken her five minutes to reach home:

Police know that Miss McDonnell had got off the 111 bus at Percy Road, close to her house in Priory Road, Hampton. They said they wanted to establish what had happened in the 15 minutes after she got off the bus and before she was found at 12.30am.

Her walk home should have taken no more than five minutes.

(Source).

It should be noted that police do not appear to posit that Bellfield himself may have been the cause for McDonnell’s delay by dint of propositioning her from his vehicle; this would perhaps spoil the theory that he stationed himself ahead of her in a side road. Perhaps what we can discern from the fact of there being no mention of it in any reportage is that neighbours, who will no doubt have been questioned, in what is a residential area with streets lined with houses, did not report hearing any vocal interchange in the street.

So, with police understanding that she had not been followed on foot from the bus, there appears to be no reason for why McDonnell, on what would be a cold February night, who had been to the cinema in Kingston (not a party, or a pub) would hang about getting home. Thus, the delay is probably explained by the bus journey taking longer than it should, or longer than police say it did.

If we examine stills from CCTV that show McDonnell about to leave the bus (from a BBC webpage) and that show the Vauxhall Corsa approaching the bus (taken from the Channel 5 programme, 5 Mistakes that Caught a Killer), we see that the latter is time stamped. This time of 00:17 is when McDonnell reportedly left the bus (from the BBC: “She got off at 00:17 GMT at Percy Road just past Priory Road, Hampton”). However, the reader will notice that there is no timestamp on the still which is presented as showing the moments when McDonnell disembarked from the bus.

Marsha McDonnell set to depart the bus. Originally published on a BBC website as shown, without a timestamp.

If the timestamp that should be on this image has actually been cropped off because McDonnell was leaving her bus later than 17 minutes past midnight – and she would only have to be anything up to seven to eight minutes late – then this would mean that the Vauxhall Corsa would have been in the vicinity of the bus at an earlier place along the route, and could not have been manoeuvring to intercept McDonnell.

Just to show that these images have a time stamp when it is convenient. Marsha McDonnell getting on the bus.

In fact, Google Maps reports that the bus journey from the Cromwell Road bus station in Kingston (which is recommended as the nearest place to catch the 111 bus from the Kingston Odeon) to the stop in Percy Road [just past Priory Road], while it often does take 9, can on occasion take up to 15 minutes (depending on the time of night and number of stops). So, if McDonnell caught the bus at eight minutes past midnight, as the official narrative has it, and she arrived at her stop at 23 minutes past midnight, leaving a more realistic 7 minutes maximum for the walk to her house, then the Vauxhall Corsa could have actually encountered the bus 6 minutes earlier back down the route.

Just by allowing that there were in fact no missing minutes for Marsha McDonnell, explained by some quirk of her particular bus journey, means that one must conclude that there is no linkage between a Vauxhall Corsa and her murder, thus there is no means to incriminate Bellfield.

But to cap it all there exists in corporate-media reportage of Bellfield’s trial a second account of how the CCTV still of the Vauxhall Astra was obtained (see the Your Local Guardian link above):

CCTV footage taken from the H22 bus as the 19-year-old was waiting for the doors to open at her stop in Priory Road, Hampton, show a car passing from the opposite direction, which the prosecution alleges was that of bouncer Levi Bellfield.

While the misidentification of the route of the bus, which might be an innocent mistake in the reporting, can perhaps be overlooked, the notion that the car came from the opposite direction as the bus was travelling destroys the claim that the person driving it could have been following Marsha McDonnell. What we might be seeing here is recognition of the image for what it is: one taken from the front, not the back of the bus, and if we could get to the bottom of how this image should be considered (there is no indicator light flashing, which is a clue in favour of a frontal approach, and against an overtaking manoeuvre from behind), we might discover that the police misrepresented evidence to force it to fit to their story. Indeed, a closer examination of the overtaking version of the story (see foot note) sees it breaking down into farfetchedness.

Indeed, it’s very hard to understand how the case against Bellfield in the McDonnell case was not ripped to tatters. In fact, it’s hard to understand how Bellfield’s defence lawyers didn’t shred any aspect of the prosecution against him in all three cases. While we have now looked at all three individually to understand this, we can also say that there is no common thread by which to convict Bellfield, because all three crimes were very different from each other: there was no standard modus operandi that could conclusively show that Bellfield was responsible for each.

McDonnell, who like Delagrange had a purse, was not the victim of a theft. The attack on Sheedy was carried out without anyone leaving a vehicle – very different to the attacks on McDonnell and Delagrange, who were struck with blunt instruments by people who had approached them on foot. Moreover, Delagrange was “followed” for 0.7 miles before she was attacked – which is perhaps not what an opportunist attacker would do. Such an attacker would have had no idea where she was heading, and while he was stalking her for so long without the opportunity to make good on the investment of time he was making, he perhaps should actually have decided to abandon the target to seek another. The time, at that point, was only between 9 and 10pm, so the night was young for his purposes. In Sheedy’s case, the attacker had a wonderful opportunity to assault her as she moved through an area that had empty spaces on either side, but he didn’t do this.

All in all, the evidence points to three perpetrators, or three sets of perpetrators, because we’ve already seen that there could have been two people in the car that ran over Sheedy. And this is where the information about Bellfield being a Metropolitan Police informant becomes very interesting. It turns out that due to his status as an intelligence asset, police turned a blind eye to his petty criminality. It also turns out that he had 42 different aliases – he would claim because of tax reasons, and because he was at a certain risk in the pursuit of his wheel clamping business from people looking for revenge. On the other hand, given that there were up to 20 people who had access to his vehicles, in the name of his business, perhaps it was just a case of him and his company as a front, and this perhaps explains why “his” vehicles could be linked with criminality that he himself didn’t necessarily commit.

But further discussion of this information and its ramifications (not to mention the recording of its sources) is the subject matter of the next and final article in this Twickenham attacks mini-series, where we are also going to tie the Bellfield phenomenon with the theory, and perhaps practical reality of military intelligence terrorising the public in the style of the Krypteia, which on a purely analytical level, even if one cannot emotionally believe it, is a highly plausible probability in terms of being statecraft for control, and for the live-exercise style training of assassins.

‡ Let’s examine this a bit more closely.

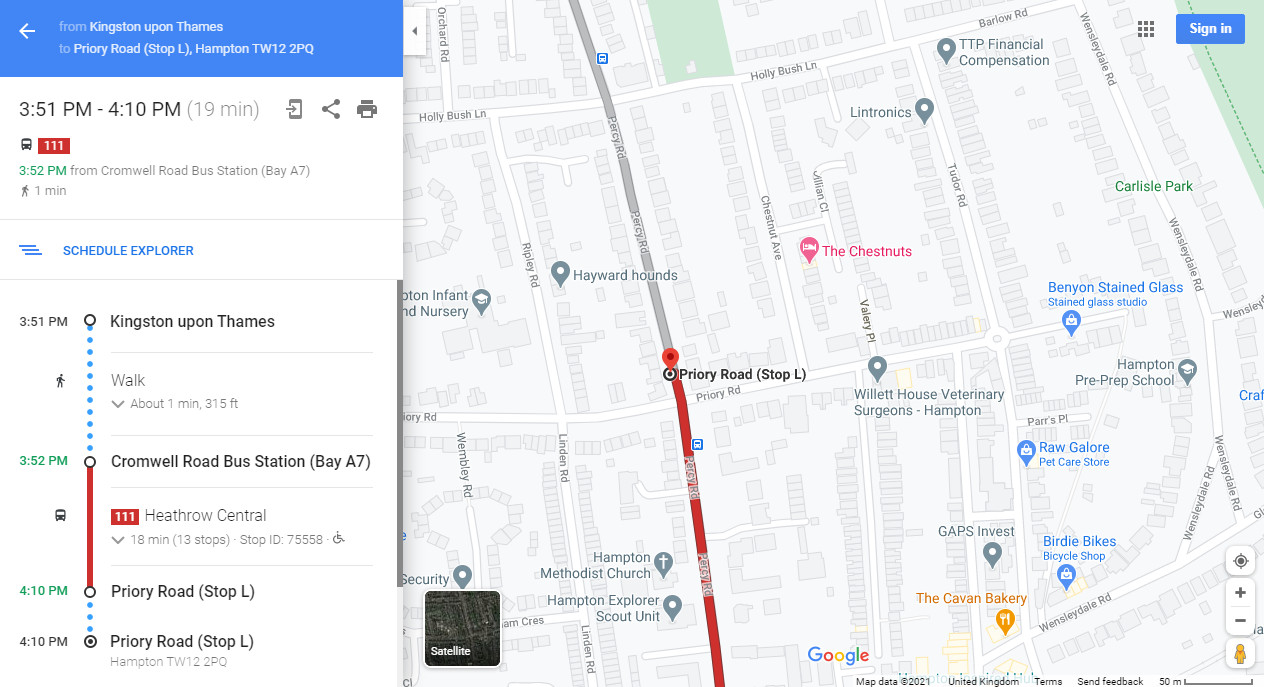

Below is a screen shot of a Google Maps directions enquiry, showing how the 111 bus comes into Percy Road, from the south, from Kingston (note the 18 minute long journey).

The stop that McDonnell would have alighted at was the one on the north side of Priory Road. So, if Bellfield was following, and overtook the bus, which near by side road was he then meant to have driven into from which he could pursue McDonnell on foot? There is none. Having seen the bus stopping, and seeing that he was approaching a crossroads, wouldn’t he have actually lingered at the junction (traffic allowing – which it very likely would have at that time of night) to see if anyone got off the bus, and to see which way they would travel?

If anyone wants to argue that he over took the bus, but actually parked the car somewhere on Priory Road, it should have been captured on the CCTV camera mounted on the front of the bus as it travelled ahead and stopped in the distance, right? Or, if the bus had a camera mounted on the back, it should have captured the car to the rear as the bus moved away along Percy Road, right?