Putting the Kherson bluff into perspective: a month of real Russian gains in northern Donetsk

Taking a short break from this site’s ongoing coverage (as far as it can be bothered with) of the recent military occurrences supposedly targeting the Kherson region of the Ukraine, this is going to be a look at the Russian advance in the north of the territory of the Donetsk People’s Republic between 8th August and 7th September (today’s date). It is very useful thing to do, especially in the light of what has been happening in Kherson.

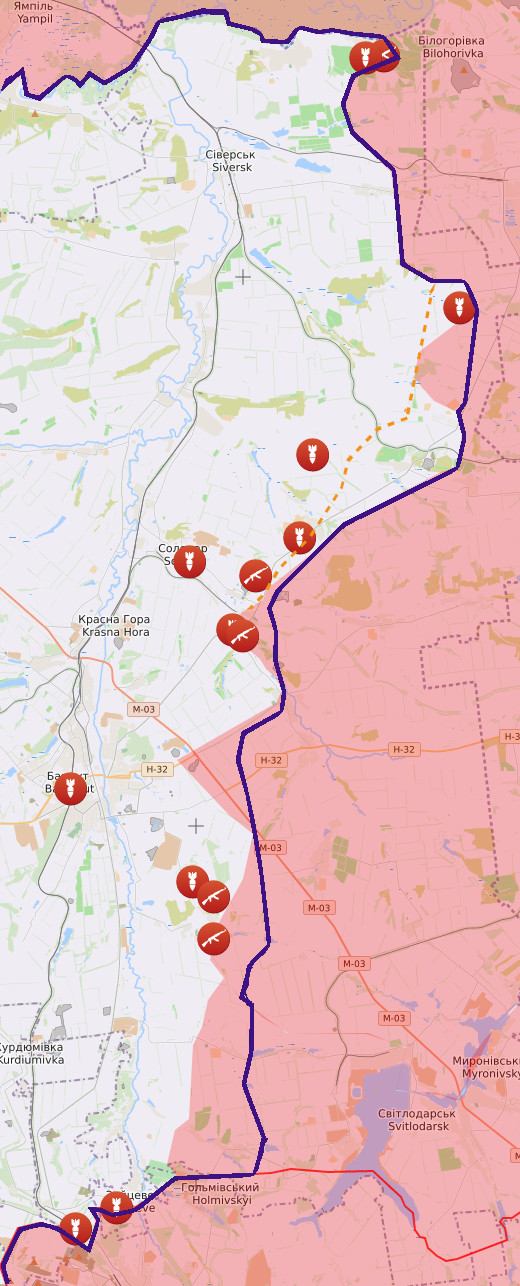

The graphic below is an amalgamation of two maps from liveuamap.com. The map itself was generated today and shows current areas of control by the Russians and allies shaded red – according to the producers of the map. The blue line represents the extent of Russian areas of control, again according to the map’s makers, as they were on 8th August. The yellow dotted line is potentially under Russian control (as far as the author can make out) according to the map presented by the Russian Ministry of Defence in that organisation’s latest briefing, and is included merely for interest. Obviously, there are other accounts of what this sector looks like, but these are irrelevant to the task (and shouldn’t be relied on, in any case). Liveuamap.com makes a great source precisely because it has Ukrainian bias, and yet has had to begrudge the Russians their gains. The point is to show that there is no denial that an advance is being made, and that the Donetsk front line is not static.

The thing that one can immediately say about this information is that, while it does not look to an untaught set of eyes as being sensational, it does signify a joined-up multiple faceted offensive all along a particular single line of front. And this allows us to put the recent Ukrainian activity into the Kherson oblast into perspective by stark contrast.

It is the author’s theory that the Ukrainians were doing three things; firstly, they were reacting to Russian gains towards Mikolaiv city; secondly, they were trying to rectify a bad position in the meanderings of the river Ingulets between Andriivka and Davydiv Brid; and thirdly, because Ukraine’s war mostly has to be a public relations one, and for political purposes, they were making smoke to give the appearance of a broader fire with other local engagement of the Russians. What they certainly did not seem to be doing was conducting a coordinated offensive at many widths along a single front. In fact, the author has no objection to the appraisal given by US officials on 30th August that the Ukrainians had begun an operation to shape the battlefield – except, as just explained, he doesn’t agree that it was for the purpose of staging a further escalation as the Americans did.

While it’s true that the Russian numbers for enemy casualties are so large‡ that they could suggest the Ukrainians had mustered with the intention of executing a major joined-up project, they are also perhaps indicative of a limited rush-and-push with high rates of attrition accounted for. After all, the Russian capability of doling out death and destruction by artillery and air power cannot at this stage have been lost on Kiev and its masters – principally the UK Government. Moreover, London and Kiev must know that they cannot reconquer Kherson. On the other hand, the objectives stated above, which amount to repositioning in order to stall the Russians all the better, and act to create an aura of success (for purposes of maintaining morale for keeping Ukraine in the fight until some miracle occurs†) would have been feasible. Indeed, if London and Kiev are working on the assumption that Moscow has no ultimate goal to conquer the Ukraine, as long as Ukraine is left with manpower to police its (reducing) male population, having large numbers killed in battle is not going to be a matter of scruple or strategy.

Contrast, then, with the Russians, and their way of fighting that is steady and not sensational, and definitely cannot tolerate over two thousand deaths over the course of five days, but instead appears to be configured to keep casualties (on the Russian’s own side) as low as possible. The Russians have a way of warfare whereby small levels of manpower can project disproportionately greater amounts of power, so naturally the design of the system would concern itself in preventing interference with capability by gaining casualties that might otherwise be considered marginal. The key is stand-off firepower, to clear a path through fortressing and mining, and to decimate the enemy force that is blocking an advance, eventually for the use of a greatly empowered mobile element to physically eject that which hasn’t died or fled. This is, at least, how the author understands the methodology. It is warfare that grinds away according to its own requirements, in the name of acquiring a goal by force. When an army can do that, it has no need for stunts gimmicks. The Russians don’t need to bluff.

‡ The total figures given in five briefings by the Russian MoD to 4th September are as follows: 126 tanks, 131 infantry fighting vehicles, 95 armoured vehicles, 2,260 persons.

† This is discussed further in other articles, see Snake Island: A “Battle Of Britain” For A Defeated Kiev; Part One: Overview Of The Myth, for instance.

You were right about one thing – the Kherson offensive was a public relations exercise – for the benefit of the Russians. You were wrong about everything else.

I have no idea what you’re talking about; this essay is about the Russian offensive in Donetsk (and in Kherson the Ukrainians lost a number of localised battles). However, I’ve published your comment because it’s a laugh, isn’t it?